United States public debt

|

| Part of a series on: |

| U.S. Budget & Debt Topics |

|---|

|

Major dimensions

|

|

Mandatory Programs

|

|

Terminology

|

The United States public debt is presented by the United States Treasury as two calculations: "Debt Held by the Public", defined as U.S. Treasury securities held by institutions outside the United States Government, and the "Gross Debt," which includes intra-government obligations (e.g., the Social Security Trust fund).[1]

As of July 28, 2010, the "Total Public Debt Outstanding" was approximately 93% of annual GDP, ($13.258 Trillion) with the constituent parts of the debt being "Debt held by the Public" being approximately 60% of GDP ($8.63 Trillion) and "Intergovernmental Debt" standing at 32% of GDP ($4.55 Trillion).[2][3] The United States has the third lowest Debt to GDP ratio of the G8 Nations (when using "Debt held by the Public" as the measure) [4] Within the remainder of this article the phrase "Public Debt" is employed as a shorthand for "Debt Held by the Public". The terms of "Debt Held by the Public" and "Total Public Debt Outstanding" are often used interchangeably, with much contention as to which is the true measure of government debt, yet what both measures share in common is that they both contain sovereign issued bonds backed by the Full Faith and Credit of the United States of America, with the differentiating factor as to who the holders of the bonds are, the "public" or "intergovernmental agencies".

The national debt should not be confused with the trade deficit, which is the difference between net imports and net exports. State and Local Government Series securities, issued by state and local governments, are not part of the United States government debt.[5]

The annual government deficit or surplus refers to the cash difference between government receipts and spending ignoring intra-governmental transfers. The gross debt increases or decreases as a result of this unified budget deficit or surplus. However, there is certain spending (supplemental appropriations) that add to the gross debt but are excluded from the deficit. The total debt has increased over $500 billion each year since fiscal year (FY) 2003, with increases of $1 trillion in FY2008 and $1.9 trillion in FY2009.[6]

Contents |

History

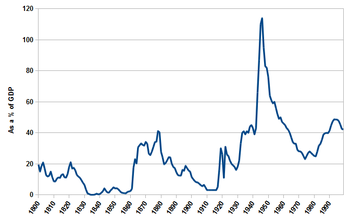

The United States has had public debt since its inception. Debts incurred during the American Revolutionary War and under the Articles of Confederation led to the first yearly reported value of $75,463,476.52 on January 1, 1791. Over the following 45 years, the debt grew, briefly contracted to zero on January 8, 1835 under President Andrew Jackson but then quickly grew into the millions again.[7]

The first dramatic growth spurt of the debt occurred because of the Civil War. The debt was just $65 million in 1860, but passed $1 billion in 1863 and had reached $2.7 billion following the war. The debt slowly fluctuated for the rest of the century, finally growing steadily in the 1910s and early 1920s to roughly $22 billion as the country paid for involvement in World War I.[7]

The buildup and involvement in World War II plus social programs during the F.D. Roosevelt and Truman presidencies in the 1930s and 40's caused a sixteenfold increase in the gross debt from $16 billion in 1930 to $260 billion in 1950.

After this period, the growth of the gross debt closely matched the rate of inflation where it tripled in size from $260 billion in 1950 to around $909 billion in 1980. Gross debt in nominal dollars quadrupled during the Reagan and Bush presidencies from 1980 to 1992. The Public debt quintupled in nominal terms.

In nominal dollars the public debt rose and then fell between 1992 and 2000 from $3T in 1992 to $3.4T in 2000. During the administration of President George W. Bush, the gross debt increased from $5.6 trillion in January 2001 to $10.7 trillion by December 2008,[8] rising from 58% of GDP to 70.2% of GDP. During March 2009, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that gross debt will rise from 70.2% of GDP in 2008 to 100.6% in 2012.[9]

| Year | Gross Debt in Billions undeflated[10] | as % of GDP | Debt Held By Public ($Billions) | as % of GDP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 2.6 | unk. | 2.6 | unk. |

| 1920 | 25.9 | unk. | 25.9 | unk. |

| 1928 | 18.5[11] | unk. | 18.5 | unk. |

| 1930 | 16.2 | unk. | 16.2 | unk. |

| 1940 | 50.6 | 52.4 | 42.8 | 44.2 |

| 1950 | 256.8 | 94.0 | 219.0 | 80.2 |

| 1960 | 290.5 | 56.0 | 236.8 | 45.6 |

| 1970 | 380.9 | 37.6 | 283.2 | 28.0 |

| 1980 | 909.0 | 33.4 | 711.9 | 26.1 |

| 1990 | 3,206.3 | 55.9 | 2,411.6 | 42.0 |

| 2000 | 5,628.7 | 58.0 | 3,409.8 | 35.1 |

| 2001 | 5,769.9 | 57.4 | 3,319.6 | 33.0 |

| 2002 | 6,198.4 | 59.7 | 3,540.4 | 34.1 |

| 2003 | 6,760.0 | 62.6 | 3,913.4 | 35.1 |

| 2004 | 7,354.7 | 63.9 | 4,295.5 | 37.3 |

| 2005 | 7,905.3 | 64.6 | 4,592.2 | 37.5 |

| 2006 | 8,451.4 | 65.0 | 4,829.0 | 37.1 |

| 2007 | 8,950.7 | 65.6 | 5,035.1 | 36.9 |

| 2008 | 9,985.8 | 70.2 | 5,802.7 | 40.8 |

| 2009 | 12,311.4 | 86.1 | 7,811.1 | 54.6 |

| 2010 (2 August) | 13,296.8 | 91.1 (2nd Q) | 8,771.7 | 60.1 (2nd Q) |

| 2010 (est.) | 14,456.3 | 98.1 | 9,881.9 | 67.1 |

| 2011 (est.) | 15,673.9 | 101.0 | 10,873.1 | 70.1 |

| 2012 (est.) | 16,565.7 | 100.6 | 11,468.4 | 69.6 |

| 2013 (est.) | 17,440.2 | 99.7 | 12,027.1 | 68.7 |

| 2014 (est.) | 18,350.0 | 99.8 | 12,594.8 | 68.5 |

Note: 2010-2014 are projections

Debt ceiling

The Second Liberty Bond Act of 1917 established a statutory limit on federal debt.[12] Congress had previously approved each debt issuance separately. The debt limit provided the U.S. Treasury with more leeway in the administration of debt, allowing for modern management techniques in government finance.

The U.S. Treasury Department now conducts more than 200 sales of debt by auction every year. The Treasury has been granted authority by Congress to issue such debt as was needed to fund government operations as long as the total debt (excepting some small special classes) does not exceed a stated ceiling.

The most recent increase in the U.S. debt ceiling to $14.3 trillion by H.J.Res. 45 was signed into law on February 12, 2010.[13]

Components

Public and government accounts

The national debt is broken down into 2 main categories:[14]

- Securities held by the public

-

- Marketable securities

- Non-marketable securities

-

- Securities held by government accounts

The values for fiscal years 1999-2008 are published by the treasury[14] and about 60% of the debt is held by the public.

As of 2008, Social Security Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund holds about half of the government held portion of the debt at 2.2 trillion dollars, with other large holders including the Federal Housing Administration, the Federal Savings and Loan Corporation's Resolution Fund and the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund. Most of the public debt is in notes and bills with only about one trillion in bonds and inflation protected bonds.

Estimated ownership

Because a large variety of people own the notes, bills, and bonds in the "public" portion of the debt, the U.S. Treasury also publishes information that groups the types of holders by general categories to portray who owns United States debt. In this data set, some of the public portion is moved and combined with the total government portion, because this amount is owned by the Federal Reserve as part of United States monetary policy. (See Federal Reserve System)

As is apparent from the chart, a little less than half of the total national debt is owed to the "Federal Reserve and intragovernmental holdings". The foreign and international holders of the debt are also put together from the notes, bills, and bonds sections. Below is a chart for the data as of June 2008:

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac obligations excluded

Although not included in the figures reported by the government, the U.S. government has moved to more explicitly support the soundness of obligations of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, starting in July 2008 via the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008, and the September 7, 2008 Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) conservatorship of both government sponsored enterprises (GSEs). The on- or off-balance sheet obligations of those two independent GSEs was just over $5 trillion at the time the conservatorship was put in place.[15]

The government accounts for these corporations as if they are unconnected to its balance sheet. At the inception of the conservatorship, the U.S. Treasury contracted to receive US$1 billion in senior preferred shares, and a warrant for 79.9% of the common shares from each GSE, as a fee to fund, as needed, up to US$100 billion total for each GSE (in exchange for more senior preferred stock), in order to maintain solvency and adequate capital ratios at the GSEs, thereby supporting all senior (normal) liabilities, subordinated indebtedness, and guarantees of the two firms. Some observers see this as an effective nationalization of the companies that ultimately places taxpayers at risk for all their liabilities[16][17]

The net exposure to taxpayers is difficult to determine at the time of the takeover and depends on several factors, such as declines in housing prices and losses on mortgage assets in the future.[18] The Congressional Budget Office has recommended incorporating the assets and liabilities of the two companies into the federal budget due to the degree of government control over the entities.[19] The 5-year credit default swap spread for U.S. treasuries had risen to 18 basis points per annum as of 9 September 2008 as a result of market perception regarding the increased debt load of the government.[19]

On January 8, 2009, Moody's said that only 4 of the 12 Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLB) may be able to maintain minimum required capital levels and the U.S. government may need to put some of them into conservatorship. [4] According to Bloomberg, the FHLB is the largest U.S. borrower after the federal government. [5]

Guaranteed obligations excluded

Starting in late 2008, the U.S. federal government is guaranteeing large amounts of obligations relating to mutual funds, banks, and corporations under several new programs designed to deal with the problems initiated by the Liquidity crisis of September 2008. Guarantees are off-balance sheet and therefore excluded in the calculation of federal debt. The funding of direct investments made in response to the crisis, such as those made under the Troubled Assets Relief Program, are captured by the debt totals.

Foreign ownership

The US debt in the hands of foreign governments was 25% of the total in 2007,[20] virtually double the 1988 figure of 13%.[21] Despite the declining willingness of foreign investors to continue investing in US dollar denominated instruments as the US dollar fell in 2007,[22] the U.S. Treasury statistics indicate that, at the end of 2006, non-US citizens and institutions held 44% of federal debt held by the public.[23] About 66% of that 44% was held by the central banks of other countries, in particular the central banks of Japan and China. In May 2009, the US owed China $772 billion.[24]

In total, lenders from Japan and China held 44% of the foreign-owned debt.[25] This exposure to potential financial or political risk should foreign banks stop buying Treasury securities or start selling them heavily was addressed in a recent report issued by the Bank of International Settlements, which stated, "'Foreign investors in U.S. dollar assets have seen big losses measured in dollars, and still bigger ones measured in their own currency. While unlikely, indeed highly improbable for public sector investors, a sudden rush for the exits cannot be ruled out completely."[26]

On May 20, 2007, Kuwait discontinued pegging its currency exclusively to the dollar, preferring to use the dollar in a basket of currencies.[27] Syria made a similar announcement on June 4, 2007.[28] In September 2009 China, India and Russia said they were interested in buying IMF gold to diversify their dollar-denominated securities.[29] However, in July 2010 China's State Administration of Foreign Exchange "ruled out the option of dumping its vast holdings of US Treasury securities" and said gold "cannot become a main channel for investing our foreign exchange reserves" because the market for gold is too small and prices are too volatile.[30]

The following is a list of the Foreign Owners of U.S. Treasury Securities as listed by the U.S. Treasury:[25]

| Leading Foreign owners of US Treasury Securities (May 2010) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Nation | billions of dollars | percentage |

| People's Republic of China (mainland) | 867.7 | 21.9 |

| Japan | 786.7 | 19.8 |

| United Kingdom | 350.0 | 8.8 |

| Brazil | 161.4 | 4.1 |

| Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (Hong Kong) | 145.7 | 3.7 |

| Russia | 126.8 | 3.2 |

| Republic of China (Taiwan) | 126.2 | 3.2 |

| Grand Total | 3963.6 | 100 |

Statistics and comparables

- U.S. official gold reserves, totaling 261.5 million troy ounces, have a book value as of 30 November 2009[update] of approximately $11 billion,[31] vs. a commodity value as of 17 December 2009[update] of approximately $288.5 billion.[32]

- A total of 161,000 tonnes of gold have been mined in human history, as of 2009.[33] This is roughly equivalent to 5.175 billion troy ounces, which, at $1000 per troy ounce, would be $5.2 trillion.

- Foreign exchange reserves $134 billion as of October 2009[update].[34]

- The Strategic Petroleum Reserve had a value of approximately $69 billion as of December 2009[update], at a Market Price of $104/barrel with a $15/barrel discount for sour crude.[35]

- The national debt equates to $30,400 per person U.S. population, or $60,100 per member of the U.S. working population,[36] as of February 2008.

- In 2008, $242 billion was spent on interest payments servicing the debt, out of a total tax revenue of $2.5 trillion, or 9.6%. Including non-cash interest accrued primarily for Social Security, interest was $454 billion or 18% of tax revenue.[37]

- Total U.S. household debt, including mortgage loan and consumer debt, was $11.4 trillion in 2005. By comparison, total U.S. household assets, including real estate, equipment, and financial instruments such as mutual funds, was $62.5 trillion in 2005.[38]

- Total U.S Consumer Credit Card revolving credit debt was $931.0 billion in April 2009.[39]

- Total third world debt was estimated to be $1.3 trillion in 1990.[40]

- The U.S. balance of trade deficit in goods and services was $725.8 billion in 2005.[41]

- The global market capitalization for all stock markets that are members of the World Federation of Exchanges was $32.5 trillion by the end of 2008.[42]

- The 2009 net worth of the 400 richest U.S. citizens is $1.27 trillion. [43]

| Gross debt as percentage of GDP | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 2011 Forecast | |

| Austria | 62% | 82% |

| France | 70% | 99% |

| Germany | 65% | 85% |

| Greece | 104% | 130% |

| Ireland | 28% | 93% |

| Italy | 112% | 130% |

| Japan | 167% | 204% |

| Netherlands | 52% | 82% |

| Portugal | 71% | 97% |

| Spain | 42% | 74% |

| United Kingdom | 47% | 71% |

| United States | 62% | 100% |

| Asia1 | 37% | 41% |

| Central Europe2 | 23% | 29% |

| Latin America3 | 41% | 35% |

Sources: IMF, World Economic Outlook (emerging market economies); OECD, Economic Outlook (advanced economies)[44]

1China, Hong Kong SAR, India, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand

2The Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland

3Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Mexico

Risks and obstacles

Risks to the U.S. dollar and economy

A high debt level can affect inflation, interest rates, and economic growth. A variety of factors are placing increasing pressure on the value of the U.S. dollar, increasing the risk of devaluation or inflation and encouraging challenges to dollar's role as the world's reserve currency. If another currency or basket of currencies replaced the dollar as the reserve currency, the U.S. would face higher interest rates to attract capital, reducing economic growth for the long-term. The Economist wrote in May 2009:

"Having spent a fortune bailing out their banks, Western governments will have to pay a price in terms of higher taxes to meet the interest on that debt. In the case of countries (like Britain and America) that have trade as well as budget deficits, those higher taxes will be needed to meet the claims of foreign creditors. Given the political implications of such austerity, the temptation will be to default by stealth, by letting their currencies depreciate. Investors are increasingly alive to this danger..."[45]

Key drivers of these risks relate to the unwillingness of the U.S. to live within its means, both from a budget deficit and trade deficit standpoint. For example, the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the Federal Government's auditor, argues that the U.S. is on a fiscally "unsustainable" path and that politicians and the electorate have been unwilling to change this path.[46] The 2010 U.S. budget indicates annual debt increases of nearly $1 trillion annually through 2019. By 2019 the total U.S. national debt is projected to be $18.4 trillion.[47] Further, the subprime mortgage crisis has significantly increased the financial burden on the U.S. government, with over $10 trillion in commitments or guarantees and $2.6 trillion in investments or expenditures as of May 2009, only some of which are included in the budget document.[48]

The U.S. also has a large trade deficit, meaning imports exceed exports. Financing these deficits requires the USA to borrow large sums from abroad, much of it from countries running trade surpluses, mainly the emerging economies in Asia and oil-exporting nations. The balance of payments identity requires that a country (such as the USA) running a current account deficit also have a capital account (investment) surplus of the same amount. In 2005, Ben Bernanke addressed the implications of the USA's high and rising current account (trade) deficit, resulting from USA imports exceeding its exports. Between 1996 and 2004, the USA current account deficit increased by $650 billion, from 1.5% to 5.8% of GDP.[49]

Debt levels may also affect economic growth rates. Economists Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart reported in 2010 that among the 20 advanced countries studied, average annual GDP growth was 3-4% when debt was relatively moderate or low (i.e. under 60% of GDP), but it dips to just 1.6% when debt was high (i.e. above 90% of GDP).[50]

Rollover and maturity risks

In addition to the debt increase required to fund government spending in excess of tax revenues during a given year, some Treasury securities issued in prior years mature and must be "rolled-over" or replaced with new security issuance. During the financial crisis, the Treasury issued a sizable amount of relatively shorter-term debt, which caused the average maturity on total Treasury debt to reach a 25-year low of just more than 50 months in 2009. As of late 2009, roughly 43% of U.S. public debt needed to be rolled over within 12 months, the highest proportion since the mid-1980s. The relatively short maturity of outstanding Treasury debt, coupled with the increased reliance on foreign creditors, puts the U.S. at greater risk of sharply higher borrowing costs should risk perceptions change abruptly in credit markets.[50]

Long-term risks to financial health of federal government

Several government agencies provide budget and debt data and analysis. These include the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), and the U.S. Treasury Department. These agencies have reported that the federal government is facing a series of critical long-term financing challenges. This is because expenditures related to entitlement programs such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are growing considerably faster than the economy overall, as the population grows older.

These agencies have indicated that under current law, sometime between 2030 and 2040, mandatory spending (primarily Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and interest on the national debt) will exceed tax revenue. In other words, all discretionary spending (e.g., defense, homeland security, law enforcement, education, etc.) will require borrowing and related deficit spending. These agencies have used such language as "unsustainable" and "trainwreck" to describe such a future.[51]

While there is significant debate about solutions,[52] the significant long-term risk posed by the increase in entitlement spending is widely recognized[53], with health care costs (Medicare and Medicaid) the primary risk category.[54][55] In a June 2010 opinion piece in the Wall Street Journal, former chairman of the Federal Reserve, Alan Greenspan noted that "Only politically toxic cuts or rationing of medical care, a marked rise in the eligible age for health and retirement benefits, or significant inflation, can close the deficit."[56] If significant reforms are not undertaken, benefits under entitlement programs will exceed government income by over $40 trillion over the next 75 years.[57] According to the GAO, this will cause debt ratios relative to GDP to double by 2040 and double again by 2060, reaching 600 percent by 2080.[58]

In 2006, Professor Laurence Kotlikoff argued the United States must eventually choose between "bankruptcy", raising taxes, or cutting payouts. He assumes there will be ever-growing payment obligations from Medicare and Medicaid.[59] Others who have attempted to bring this issue to the fore of America's attention range from Ross Perot in his 1992 Presidential bid, to motivational speaker Robert Kiyosaki, and David Walker, former head of the Government Accountability Office.[60][61]

Thomas Friedman has argued that increasing dependence on foreign sources of funding will render the U.S. less able to act independently.[62]

Moody's Investors Service warned in March 2010 that the United State's AAA-rated U.S Treasury bonds that while currently not in danger, could be downgraded in the future if the U.S. government failed to reign in public debt, saying that growing the economy can not be the only solution.[63]

Unfunded obligations

The U.S. government is committed under current law to mandatory payments for programs such as Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security. The GAO projects that payouts for these programs will significantly exceed tax revenues over the next 75 years. The Medicare Part A (hospital insurance) payouts already exceed program tax revenues and Social Security payroll taxes fully cover payouts only until 2017. These deficits require funding from other tax sources or borrowing.[51]

The present value of these deficits or unfunded obligations is an estimated $45.8 trillion. This is the amount that would have to be set aside during 2009 such that the principal and interest would pay for the unfunded commitments through 2084. Approximately $7.7 trillion relates to Social Security, while $38.2 trillion relates to Medicare and Medicaid. In other words, health care programs are nearly five times as serious a funding challenge as Social Security. Adding this to the national debt and other federal commitments brings the total obligations to nearly $62 trillion.[64]

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has indicated that: "Future growth in spending per beneficiary for Medicare and Medicaid—the federal government’s major health care programs—will be the most important determinant of long-term trends in federal spending. Changing those programs in ways that reduce the growth of costs—which will be difficult, in part because of the complexity of health policy choices—is ultimately the nation’s central long-term challenge in setting federal fiscal policy."[65]

Recent additions to the public debt of the United States

| Fiscal year (begins 10/01 of prev. year) |

Value | % of GDP |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | $144.5 billion | 1.4% |

| 2002 | $409.5 billion | 3.9% |

| 2003 | $589.0 billion | 5.5% |

| 2004 | $605.0 billion | 5.3% |

| 2005 | $523.0 billion | 4.3% |

| 2006 | $536.5 billion | 4.1% |

| 2007 | $459.5 billion | 3.4% |

| 2008 | $1017.0 billion | (proj.) 7.4% |

There is a significant difference between the reported budget deficit and the change in debt. The key differences are: 1) The Social Security surplus, which reduces the "off-budget" deficit often reported in the media; and 2) Non-budgeted spending, such as for the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. The debt increased by approximately $550 billion on average each year during the 2003-2007 period, but then increased over $1 trillion during FY 2008.

The cumulative debt of the United States in the past 8 completed fiscal years was approximately $4.3 trillion, or about 43% of the total national debt of ~$10.0 trillion as of September 2008.[66][67]

Interest expense

Budgeted net interest on the public debt was approximately $240 billion in fiscal years 2007 and 2008. This represented approximately 9.5% of government spending. Interest was the fourth largest single budgeted disbursement category, after defense, Social Security, and Medicare.[68] Despite higher debt levels, this declined to $189 billion in 2009 or approximately 5% of spending, due to lower interest rates. Average interest rates declined due to the crisis from 1.6% in 2008 to 0.3% in 2009.[69]

During FY2008, the government also accrued a non-cash interest expense of $212 billion for intra-governmental debt, primarily the Social Security Trust Fund, for a total interest expense of $454 billion.[70] This accrued interest is added to the Social Security Trust Fund and therefore the national debt each year and will be paid to Social Security recipients in the future.

Public debt owned by foreigners has increased to approximately 50% of the total or approximately $3.4 trillion.[71] As a result, nearly 50% of the interest payments are now leaving the country, which is different from past years when interest was paid to U.S. citizens holding the public debt. Interest expenses are projected to grow dramatically as the U.S. debt increases and interest rates rise from very low levels in 2009 to more typical historical levels. CBO estimates that nearly half of the debt increases over the 2009-2019 period will be due to interest.[72]

Should interest rates return to historical averages, the interest cost would increase dramatically. Historian Niall Ferguson described the risk that foreign investors would demand higher interest rates as the U.S. debt levels increase over time in a November 2009 interview.[73]

Debt clocks

In several cities around the United States, there are national debt clocks—electronic billboards that illustrate government debt. Some also attempt to show the money owed per capita or per family. There is a significant level of fluctuation day-to-day, both up and down, so any "clocks" must be continually re-set with proper values.

The first and most famous debt clock, the National Debt Clock located near Times Square in New York City, was created by real estate investor Seymour Durst.[74][75] With Seymour's death, his son Douglas Durst took over responsibility for the clock through the Durst Organization.

Although the total debt continued to increase, the clock was deactivated in 2000 when the public debt began to decrease due to budget surpluses.[76] However, following large increases in the debt (total and public) a few years later, the clock was reactivated in July 2002.[77]

In 2004, the original clock was unmounted from its location near 42nd Street; the building has since made way for One Bryant Park. An updated model, which could run backwards, was installed one block away on a Durst building at 1133 Avenue of the Americas. Since September 30, 2008, when the debt surpassed $10 trillion, the clock's dollar sign has been replaced by the extra digit. An upgrade adding to the digits had been announced for 2009, but so far has not been undertaken.

Calculating and projecting the debt

| Error creating thumbnail: convert: unable to open image `/var/www/mirror/commons_wikimedia_org/images/thumb/8/80/Debt_and_Debt_%%_to_GDP_-_2010_Budget.png/250px-Debt_and_Debt_%%_to_GDP_-_2010_Budget.png': No such file or directory @ blob.c/OpenBlob/2480. |

Tracking current levels of debt is a cumbersome but rather straightforward process. Making future projections is much more difficult for a number of reasons. For example, before the September 11, 2001 attacks, the George W. Bush administration projected in the 2002 budget that there would be a $1.288 trillion surplus from 2001 through 2004.[78]

In the 2005 Mid-Session Review, however, this had changed to a projected deficit of $850 billion, a swing of $2.138 trillion.[79] The latter document states that 49 percent of this swing was due to "economic and technical re-estimates", 29 percent was due to "tax relief", (mainly the 2001 and 2003 Bush tax cuts), and the remaining 22 percent was due to "war, homeland, and other enacted legislation" (mainly expenditures for the War on Terror, Iraq War, and homeland security).

Projections between different groups will sometimes differ because they make different assumptions. For example, in August 2003, a Congressional Budget Office report projected a $1.4 trillion deficit from 2004 through 2013.[80]

However, a mid-term and long-term joint analysis a month later by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, the Committee for Economic Development, and the Concord Coalition stated that "In projecting deficits, CBO follows mechanical 'baseline' rules that do not allow it to account for the costs of any prospective tax or entitlement legislation, no matter how likely the enactment of such legislation may be." The analysis added in a proposed tax cut extension and Alternative Minimum Tax reform (enacted by a 2005 act), prescription drug plan (Medicare Part D, enacted in a 2003 act), and further increases in defense, homeland security, international, and domestic spending. According to the report, this "adjusts CBO's official ten-year projections for more realistic assumptions about the costs of budget policies", raising the projected deficit from $1.4 trillion to $5 trillion.[81]

The 2010 Budget proposed by President Barack Obama projects significant debt increases, both in terms of dollars and relative to GDP.[82][83] The debt is projected to nearly double to $20 trillion by 2015, but is expected to increase to nearly 100% of GDP by 2020 and remain at that level thereafter. These estimates assume real GDP growth (after inflation) ranging from 2.6% to 4.6% annually from 2010 through 2019, which exceeds Blue Chip consensus estimates.[84]

During FY 2008, approximately 76.6% of federal spending was in the following categories: Departments of Health and Human Services (19.8%), Defense (20.3%) and Veterans Affairs (11.8%); Social Security Administration (18.2%); interest on the public debt (6.6%).[85]

The Office of Management and Budget forecasts that, by the end of fiscal year 2012, gross federal debt will total $16.3 trillion. Thus, the debt will equal 101% of gross domestic product, which represents a milestone in the U.S. economy. Public debt alone, which excludes amounts that the government owes its citizens via various trust funds, will be 67% of GDP by the end of fiscal 2012.[86]

Monitoring the risks of increasing debt levels

Various financial indicators may provide an early warning that market forces are reacting to an increasing level of debt. Examples include Treasury security interest rates (yields), Treasury auction results, credit default swap spreads, and TIPS spreads.

- Treasury note yields: A rising yield for a security of a given maturity could indicate lower demand for Treasury bonds among investors, or nervousness about future rates of inflation. The "yield curve" (a graph that relates the yields of similar securities of different maturities) provides similar information.

- Treasury auctions: The ease with which new securities can be sold reflects the demand for them. For example, a difference between the interest rate that debt trades prior to auction and the yield required to clear the market at auction is called the "tail." A large auction “tail” would be a sign of declining interest from the market. The Treasury also reports the bid-to-cover ratio for each auction, which is the number of market bids received relative to the number of bids accepted and the ratio of international buyers.

- Credit default swap (CDS) spreads: CDS are insurance-like derivative products that offer protection against bond defaults. CDS spreads essentially measure the current market price of insurance against default. When the market perceives a bond is at an increased risk of default, the CDS written on those bonds will increase in price.

- TIPS spreads: A key measure of inflation expectations among U.S. bond market investors is the difference between the yield on nominal Treasury bonds and the yield for Treasury inflation-protected securities, or “TIPS.” This difference is a gauge of investors’ beliefs about future U.S. inflation rates. A growing spread between nominal Treasuries and TIPS would indicate that investors are concerned that U.S. fiscal and monetary policy could lead to higher inflation in the future.[87]

Debate regarding a "danger level" of debt

Economists debate the level of debt relative to GDP that signals a "red line" or dangerous level, or if any such level exists. Economists Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart reported in January 2010 that 90% of GDP represents this danger level.[88] Reinhart testified to the U.S. Senate in February 2010, stating:[89]

Our main finding is that across both advanced countries and emerging markets, high debt/GDP levels (90 percent and above) are associated with notably lower growth outcomes. Above 90 percent, median growth rates fall one percent, and average growth falls considerably more. In addition, for emerging markets, there appears to be a more stringent threshold for total external debt/GDP; when external debt reaches 60 percent of GDP, annual growth declines by about two percent and for higher levels, growth rates are roughly cut in half. Seldom do countries simply 'grow' their way out of deep debt burdens.

Economist Paul Krugman disputed the existence of a solid debt threshold or danger level, arguing that low growth causes high debt rather than the other way around.[90] He also points out that in Europe, Japan, and the US this has been the case. In the US the only period of debt over 90% of GDP was after World War II when "when real GDP was falling, not because of debt problems, but because wartime mobilization was winding down and Rosie the Riveter was becoming a suburban housewife."[91] Fed Chair Ben Bernanke stated in April 2010:[92]

Neither experience nor economic theory clearly indicates the threshold at which government debt begins to endanger prosperity and economic stability. But given the significant costs and risks associated with a rapidly rising federal debt, our nation should soon put in place a credible plan for reducing deficits to sustainable levels over time.

There is also a second debate regarding whether debt held by the public (a lower amount) or gross debt (a larger amount) is the appropriate measure to use in evaluating the debt burden, measured as a percent of GDP. Krugman argued in May 2010 that the debt held by the public is the right measure to use, while Reinhart has testified to the President's Fiscal Reform Commission that gross debt is the right figure. Certain members of the Commission are focusing on gross debt.[90] The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) cited research by several economists supporting the use of the lower debt held by the public figure as a more accurate measure of the debt burden, disagreeing with these Commission members.[93]

This second debate relates to the economic nature of the intragovernmental debt that represents the difference between the two debt figures. As of April 30, 2010 the public debt was $8.4 trillion (59% GDP) and the gross debt was $12.9 trillion (90% of GDP), using a $14.3 trillion GDP estimate. The difference is the $4.5 trillion intra-governmental debt, mainly represented by the Social Security Trust Fund.[94]

For example, the CBPP argues:[93]

Debt held by the public is important because it reflects the extent to which the government goes into private credit markets to borrow. Such borrowing draws on private national saving and international saving, and therefore competes with investment in the nongovernmental sector (for factories and equipment, research and development, housing, and so forth). Large increases in such borrowing can also push up interest rates and increase the amount of future interest payments the federal government must make to lenders outside of the United States, which reduces Americans’ income. By contrast, intragovernmental debt (the other component of the gross debt) has no such effects because it is simply money the federal government owes (and pays interest on) to itself.

Current projections indicate the lower debt held by the public figure will hit 90% of GDP by 2020.[95]

See also

US topics:

- History of the U.S. public debt - a table containing historical debt data

- Financial position of the United States

- National debt by U.S. presidential terms

- Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 - part of the Troubled Asset Relief Program

- United States federal budget - analysis of federal budget spending and long-term risks

- Economy of the United States - discusses U.S. national debt and economic context

General:

- Public debt - a general discussion of the topic

- Balance of payments

- Budget deficit

- Deficit

- Inflation

- Securities

- National bankruptcy

- Fiat currency

International:

- Global debt

- List of public debt - list of the public debt for many nations, as a percentage of the GDP

References

- ↑ Treasury Faq

- ↑ The Daily History of the Debt at Treasury Direct

- ↑ Bureau of Economic Analysis: Gross Domestic Product

- ↑ U.S. Debt Clock

- ↑ US GAO Financial Audit: Bureau of the Public Debt's Fiscal Years 2004 and 2003 Schedules of Federal Debt GAO-05-116 November 5, 2004.

- ↑ Treasury Direct

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 TreasuryDirect. Government - Historical Debt Outstanding – Annual. United States Department of the Treasury.

- ↑ Bureau of the Public Debt - Input Dates 1/1/2001 and 12/31/2008

- ↑ Table 1-1 : Comparison of Projected Revenues, Outlays, and Deficits in CBO’s March 2009 Baseline and CBO’s Estimate of the President’s Budget

- ↑ FY 2010 Budget Historical Tables Pages 127-128

- ↑ Frank H. Vizetelly, Litt.D., LL.D., ed (1931). "DEBT, National". New Standard Encyclopedia of Universal Knowledge. Eight. "New York and London": Funk and Wagnalls Company. pp. 471. "Debt of Principal Nations and Aggregate for All Nations of the World at Various Dates (in millions of dollars): "1928........18,510"".

- ↑ P.L. 65-43, 40 Stat. 288, enacted September 24, 1917. Currently codified as amended as 31 U.S.C. § 3101.

- ↑ Obama signs debt limit-paygo bill into law

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Back Issues: Treasury Bulletin: Publications & Guidance: Financial Management Service

- ↑ Paulson readies the 'bazooka', CNNMoney, 6 September 2008

- ↑ US rescue of Fannie, Freddie poses taxpayer risks, Associated Press, 8 September 2008

- ↑ Fannie Mae Enron, the Sequel, 17 Aug 2009, Wall Street Journal

- ↑ Taxpayers take on trillions in risk in Fannie, Freddie takeover (October 20, 2008), USA Today.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Kopecki, Dawn (2008-09-11). "U.S. Considers Bringing Fannie, Freddie on to Budget". Bloomberg. http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601109&sid=adr.czwVm3ws&refer=home. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ↑ Just who owns the U.S. national debt? - Answer desk - MSNBC.com

- ↑ Amadeo, Kimberly. "The U.S. Debt and How It Got So Big". About.com. http://useconomy.about.com/od/fiscalpolicy/p/US_Debt.htm. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- ↑ ParaPundit: Foreign Investment In US Declines With Dollar Decline

- ↑ Analytical Perspectives of the FY 2008 Budget

- ↑ "Retired Military Personnel". Patrick Air Force Base, Florida: The Intercom (publication of the Military Officers Association of Cape Canaveral). June 2009. pp. 4.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Major Foreign holders of U.S. Treasury Securities (2008), U.S. Treasury Department.

- ↑ BIS says global downturn could be 'deeper and more protracted' than expected - Forbes.com

- ↑ Kuwait pegs dinar to basket of currencies - Forbes.com

- ↑ "Bloomberg.com: Worldwide". http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601087&sid=ahGpyu4D9xBk&refer=worldwide. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- ↑ The Associated Press. "IMF takes up gold sales to expand lending". http://www.google.com/hostednews/ap/article/ALeqM5gnGzlhHF6ANMbHrkPv0CNDKo5lJAD9APUM1G0. Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- ↑ "China won't dump US Treasuries or pile into gold". China Daily eClips. 2010-07-18. http://www.cdeclips.com/en/business/fullstory.html?id=47499#. Retrieved 2010-07-18.

- ↑ "Status Report of U.S. Treasury-Owned Gold". http://www.fms.treas.gov/gold/current.html. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ↑ Spot Gold Price, goldprice.org

- ↑ National Geographic: "The Real Price of Gold" by Brook Larmer

- ↑ Time Series Data on International Reserves and Foreign Currency Liquidity : Official Reserve Assets, International Monetary Fund.

- ↑ Strategic petroleum reserve Inventory, Department of Energy;

^ "Sweet and sour crude". http://www.econbrowser.com/archives/2005/08/sweet_and_sour.html. Retrieved 2008-09-10. - ↑ Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey Overview

- ↑ GAO Audit Report 2007-2008 Schedules of Public Debt

- ↑ FRB: Z.1 Release- Flow of Funds Accounts of the United States, Release Dates

- ↑ "FRB: G.19 Release-Consumer Credit". http://www.federalreserve.gov/RELEASES/g19/. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- ↑ Third World Debt, by Kenneth Rogoff: The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics: Library of Economics and Liberty

- ↑ FTD - Statistics - Trade Highlights - 2004 Annual Highlights

- ↑ 2008 WFE Annual Report, p. 84 (World Federation of Exchanges)

- ↑ The Forbes 400

- ↑ The Future of Public Debt: Prospects and Implications (PDF). Bank for International Settlements. March 26, 2010.

- ↑ Economist-A New Global System is Coming Into Existence

- ↑ Citizen's Guide 2008

- ↑ 2010 Budget-Schedule S-14

- ↑ CNN Bailout Tracker

- ↑ "Bernanke-The Global Saving Glut and U.S. Current Account Deficit". Federalreserve.gov. http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/2005/20050414/default.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 U.S. House of Representatives Republican Caucus-The Perils of Rising Government Debt-May 2010

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 GAO Citizens Guide

- ↑ Bittle, Scott & Johnson, Jean. "Where Does the Money Go?" Collins; New York: 2008.

- ↑ FRB: Speech-Bernanke, The Coming Demographic Transition: Will We Treat Future Generations Fairly?-October 4, 2006

- ↑ U.S. Heading For Financial Trouble?, Comptroller Says Medicare Program Endangers Financial Stability - CBS News

- ↑ 2007 Report of the U.S. Government

- ↑ http://online.wsj.com/article/NA_WSJ_PUB:SB10001424052748704198004575310962247772540.html Alan Greenspan: US Debt and the Greece Analogy

- ↑ 2007 Report of the U.S. Government Page 47

- ↑ GAO Citizen's Guide

- ↑ Is the United States Bankrupt?

- ↑ Yahoo! Personal Finance: Calculators,Money Advice,Guides,& More

- ↑ America The Bankrupt, GAO Head Takes Fiscal Show On The Road To Warn Of Trouble Ahead - CBS News

- ↑ Friedman - Loss of Sovereignty

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/16/business/global/16rating.html?_r=1

- ↑ Peter G. Peterson Foundation-Citizen's Guide 2010-Figure 10

- ↑ CBO Testimony

- ↑ U.S. Treasury website

- ↑ Bureau of Economic Analysis

- ↑ President's Budget Page 26

- ↑ GAO Audit Report-FY2009

- ↑ GAO Audit Report

- ↑ Treasury-Major Foreign Holders of Treasury Securities

- ↑ CNN $4.8 trillion-Interest on U.S. debt-Nov 2009

- ↑ Charlie Rose Interview-Niall Ferguson-November 3, 2009

- ↑ Haberman, Clyde (March 24, 2006). "We Will Bury You, in Debt". The New York Times. http://select.nytimes.com/2006/03/24/nyregion/24nyc.html?scp=16&sq=National%20Debt%20Clock&st=cse. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- ↑ The $8.3 Trillion Debt Clock | TheLedger.com

- ↑ Budget Tables pp. 127-128

- ↑ Storey, Phil (Summer 2005). "Casting a Long Shadow". greenatworkmag.com. http://www.greenatworkmag.com/gwsubaccess/05summer/cover.html. Retrieved 2010-02-09.

- ↑ "Fiscal Year 2000: Budget of the United States Government." Office of Management and Budget, Executive Office of the President. Government Printing Office 2003. 2002 U.S. Budget.

- ↑ "Fiscal Year 2005 Mid-Session Review: Budget of the United States Government." Office of Management and Budget, Executive Office of the President. 2005. Fiscal year 2005 : Midsession Review : Budget of the U.S. Government, Office of Management and Budget, July 30, 2004 (archived from http://a255.g.akamaitech.net/7/255/2422/30jul20041200/www.gpoaccess.gov/usbudget/fy05/pdf/05msr.pdf the original] on 2008-02-27).

- ↑ "The Budget and Economic Outlook: An Update." Congressional Budget Office, Congress of the United States. August 2003 [1]

- ↑ "Mid-term and long-term deficit projections." Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Committee for Economic Development, and Concord Coalition. 29 Sept. 2003.[2]

- ↑ 2010 Budget

- ↑ Washington Post-Montgomery-Battle Lines Quickly Set Over Planned Policy Shifts

- ↑ 2010 Budget-Schedules S13 and S14

- ↑ Chart 4 in A citizen's Guide to the Financial Report of the U.S. Government, General Accounting Office.

- ↑ http://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/statements/2010/mar/26/john-boehner/boehner-says-federal-debt-will-equal-gdp-two-years/

- ↑ U.S. House of Representatives-Republican Caucus-The Perils of Rising Government Debt-May 2010

- ↑ NBER Digest-Growth in a Time of Debt-Reinhart and Rogoff-May 2010

- ↑ Reinhart Testimony to Senate-February 2010

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 Paul Krugman-Bad Analysis at the Deficit Commission-The Conscience of a Liberal Blog-May 2010

- ↑ [3]

- ↑ Speech before the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform-April 2010

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Center on Budget and Policy Priorities-Recommendation That President’s Fiscal Commission Focus on Gross Debt Is Misguided-May 2010

- ↑ Treasury Direct-Monthly Statement of Public Debt of the United States

- ↑ The Fiscal Times-Alarming Gross Debt Sparks Fiscal Commission Debate-May 27, 2010

- Wright, Robert (2008). One Nation Under Debt: Hamilton, Jefferson, and the History of What We Owe. Mc-Graw Hill. ISBN 0071543937.Argues that America completely paid off its first national debt but is unlikely to do so again.

- Bonner, William; Wiggin, Addison (2006). Empire of Debt: the Rise of an Epic Financial Crisis. Wiley. ISBN 047178253X. Argues that America is a world empire that uses credit in lieu of tribute and that history shows this to be unsustainable.

- Cavanaugh, Frances X. (1996). The Truth About the National Debt: Five Myths and One Reality. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press. ISBN 087584734X. Argues that the US is in good economic condition and that talk of the consequences of its debt is unduly alarmist.

- Hargreaves, Eric L. (1966). The National Debt.

- Macdonald, James (2006). A Free Nation Deep in Debt: The Financial Roots of Democracy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-12632-1. Argues that democracies eventually defeat autocracies because "countries with representative institutions are able to borrow more cheaply than those with autocratic governments" (p. 4). Bond markets also strengthen democracies internally by giving citizens some of the proverbial power of the purse and by aligning their interests with those of their governments.

- Rothbard, Murray Newton (1994). The Case Against the Fed. Auburn, AL: Ludwig Von Mises Institute. ISBN 094546617X. Describes the process of debt monetization by a nation's central bank and it's unfortunate consequences on society.

- Taylor, George Rogers (ed.) (1950). Hamilton and the National Debt.

External links

- Documentary about the debt, "Ten Trillion and Counting", by PBS Frontline

- Bureau of the Public Debt

- The United States Public Debt, 1861 to 1975

- GAO Citizen's Guide - 2008

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||